In the beginning…

People have lived in North Wales for a quarter of a million years. Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers foraged the coastline and valleys, and the Britain’s oldest Neanderthal remains were found in Pontnewydd near St Asaph.

A succession of Ice Ages made Britain uninhabitable, but when the last one ended around 15,000 years ago, our homo sapiens ancestors were back for good. By 5,000BC they were knocking out stone tools at the Graiglwyd axe factory at Penmaenmawr, and exporting them all over Britain.

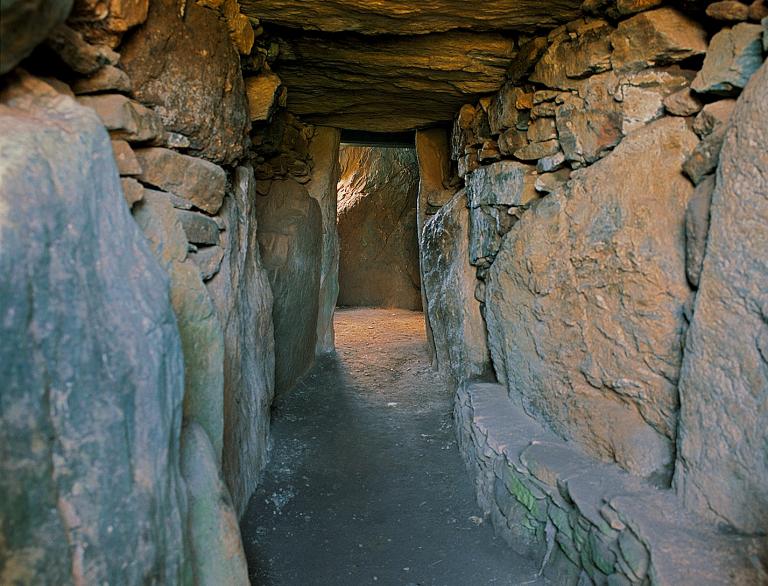

The region is scattered with Neolithic remains, especially on Anglesey, where you’ll find impressive tombs like Bryn Celli Ddu and Barclodiad y Gawres.

Metal masters

The copper mine at Great Orme was one of the most important in Europe. From 2,000BC, an estimated 1,800 tons of copper was hewn from deep tunnels. Combined with tin from Cornwall, the resulting alloy ushered in a new era known as (*drum roll*)... the Bronze Age.

It didn’t last. The Iron Age was in full swing by 800BC, and with it a fashion for building forts on every available hill. There are literally hundreds in North Wales, so it’s hard to pick highlights: try Penycloddiau in the Clwydian Range or Tre'r Ceiri up on the heights of the Llŷn Peninsula.

The Age of Celts

Were the Celts a distinct people, or was Celtic culture just transmitted from Europe? It’s a question that causes academic fisticuffs, so we’ll pass on that one. But when the Welsh identify as ‘Celtic’ (which we mostly do), we’re thinking of the Celtic tribes who lived here in the last millennium BC. In North Wales, that’s the Deceangli, Ordovices and Gangani.

They spoke Common Brittonic, the language from which modern Welsh is descended. So if you want to speak proper British (or at least, the next best thing), then sign up immediately at the National Welsh Language and Heritage Centre at Nant Gwrtheyrn.

Here come the Romans…

The island of Mona – Anglesey in English, Ynys Môn in Welsh - was the stronghold of the druids, the Celtic priests. The Romans invaded Wales in 48AD and, 30 years later, Mona was the last place to fall. The Roman historian Tacitus wrote a vivid account of the bloodcurdling sight of the warlike Celts, and the slaughter that followed. It’s a nifty bit of propaganda: the natives were wild and uncivilised, and deserved to be tamed, apparently. (Note to Romans: YOU MISSED A FEW OF US.)

Anglesey fell, but in Welsh retains its original name: Ynys Môn. The Romans built a fort at Caernarfon called Segontium, which they garrisoned until 394AD, before abandoning Britain.

King Arthur and the Saxons

After the Romans left, Britain was divided up into little kingdoms. Then came another invasion: this time by the Germanic tribes – Saxons, Angles, Jutes – who would eventually become the English. The native British were overrun or driven back to the western fringes, and given a new name: Wealas, meaning ‘foreigners’, from which the word ‘Welsh’ comes. Honestly, the cheek. Interestingly, the modern Welsh word Saeson means both ‘Saxon’ and ‘English’.

The Welsh/Brits did put up a fight, though. One shadowy hero – Arthur - was praised for his bravery in battle against the invaders in a Welsh-language poem of the era. You can learn more about him – and the places in North Wales associated with Arthur - in this article about discovering King Arthur on our website.

The Vikings arrive… and so do the Normans

The Vikings raided North Wales from the ninth century, and left their linguistic footprint in places like Anglesey (Ongle’s Ey) and Llandudno’s Great Orme (an ‘orme’ being a sea-serpent). Anglesey may even have been part of the Norse ‘Kingdom of the Isles’. The Vikings helped, temporarily at least, to halt the Norman invasion of Wales.

In 1098, Hugh of Montgomery was trying to defend the newly-conquered Anglesey when he bumped into a raiding party led by Magnus Barefoot. Magnus shot him through the eye with an arrow. As a direct result, Gruffudd ap Cynan (1055-1137) was restored as King of Gwynedd, and was de facto King of Wales until his death. He’s buried at Bangor Cathedral.

The Age of Princes

William the Conqueror never set out to conquer Wales – only England – and for the next few hundred years the Welsh settled into an uneasy relationship with their new neighbours. Wales was controlled by principalities who built castles to keep the Norman, and each other, in check. Gwynedd was the most powerful princedom, and its lords had a knack of building forts in the loveliest places – check out Castell y Bere, Dolwyddelan, Dolbadarn and Castell Dinas Brân.

The Castles of Edward I

Edward won’t win any popularity prizes in Wales, but he could build a castle (or rather his master builder, James of St George, certainly knew his stuff). During his conquest of Wales in 1277-83, Edward began building a chain of fortresses that are among the finest in the world. Four of them - Conwy, Harlech, Caernarfon and Beaumaris form a UNESCO World Heritage Site. All were besieged by Owain Glyndŵr during his uprising in 1400-15; of the four, only Caernarfon remained unbreached.

The Industrial Revolution

There were once 60 coal pits working two seams in North Wales, and the thriving Bersham Heritage Centre & Ironworks near Wrexham, but it’s the slate industry that made the biggest impression here. Entire mountains have been chewed away by quarries and mines that once produced at 485,000 tons of slate a year and employed 17,000 men. Their story is told brilliantly at the National Slate Museum, based in the old Dinorwig quarry.

The slate was hauled to sea ports by light railways, several of which – like the Talyllyn and Ffestiniog & Welsh Highland railways – have been beautifully preserved. Coal and iron trade left another superb landmark in the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct.

Grand designs

The old aristocracy and new industrial barons acquired huge wealth from their estates and quarries, which they lavished on castles and country houses. Powis Castle has priceless treasures from Clive of India’s conquests, Plas Newydd County house & Gardens has terrific art and historical collections, while Erddig specialises in the ‘upstairs-downstairs’ relationship between the master and servant classes.

Penrhyn Castle was built by wealth dubiously acquired through slavery in Jamaica and hard labour in local slate quarries, which its National Trust custodians unflinchingly recount. Whatever their origins, they’re all lovely places to visit today.

The 20th century

Here’s a quiz question: who is the only British prime minister to have spoken English as his second language? That’ll be David Lloyd George, who grew up in the little Welsh-speaking village of Llanystumdwy, where his childhood home is now the Lloyd George Museum.

He built a local reputation as a campaigner for equality and reform, and was elected to parliament in 1890 by a tiny margin of 18 votes. He served as prime minister from 1916 to 1922, leading the country through the end of the First World War and the tricky aftermath. The social reforms that he pioneered laid the foundation for many of the freedoms we take for granted today.